| . |  |

. |

Knoxville TN (SPX) Apr 07, 2006 One major looming problem for future astronauts descending on the Moon for long-term missions could be the persistence and pervasiveness of the extremely dusty lunar soil - a hazard first encountered in the early 1970s, when six Apollo missions landed on Earth's only natural satellite. The Apollo astronauts learned first-hand how moondust can be a major nuisance, because the fine powdery grit got into everything. It plugged bolt holes, fouled their tools, coated their visors and abraded their gloves. Very often while working on the surface, they had to stop to clean their cameras and equipment using large - and mostly ineffective - brushes. Simply blowing the dust out of the way in the absence of a lunar atmosphere was not an option. Now that the United States and several other nations are contemplating returning to the Moon within 20 years and staying there, dealing with the dust problem must occupy a priority for the next generation of space explorers. One researcher thinks he has found the solution to the problem: magnets. "I didn't appreciate what I had discovered," said Larry Taylor of the Planetary Geosciences Institute at the University of Tennessee. "I was explaining it to Apollo 17 astronaut Jack Schmitt one day in my office, and he said, 'Gads, just think what we could have done with a brush with a magnet attached!'" Taylor said the idea came to him in 2000, when he was in his lab studying a moondust sample from Apollo 17. Curious to see what would happen, he ran a magnet through the dust. To his surprise, he found that "all of the little grains jumped up and stuck to the magnet." He said only the finest grains - less than 20 microns in size - responded completely to the magnet, but that is not a disadvantage, because the finest dust often has been the most troublesome. Fine grains were more likely to penetrate seals at the joints of spacesuits and around the lids of pristine sample containers. When the astronauts returned to their Lunar Module wearing their dusty boots, the finest grains billowed into the air where they could be inhaled. This gave Schmitt and the others a case of what they called "moondust hay fever." Taylor said he since has designed a prototype air filter with permanent magnets inside. "When the filter gets dirty, you pull the magnets out, and the dust falls into a box," he said, adding that a later design with electromagnets worked more efficiently. "You pull the plug on the electromagnet, tap it, and the dust rains down into a container." Now, Taylor is working on a prototype design for a moondust brush using permanent magnets. "Moondust is strange stuff," he said. "Each little grain of moondust is coated with a layer of glass only a few hundred nanometers thick (1/100th the diameter of a human hair)." Taylor and colleagues have examined the coating through a microscope and found "millions of tiny specks of iron suspended in the glass like stars in the sky." Those iron specks are the source of the magnetism. Scientists think the glass content in the dust is a by-product of bombardment. Tiny micrometeorites hit the surface of the Moon, generating temperatures hotter than 2,000 degrees Celsius (3,632 degrees Fahrenheit) - literally the surface temperature of red stars. Such extreme heat vaporizes molecules in the melted soil. "The vapors consist of compounds such as (iron oxide) and (silicon dioxide)," Taylor said. If the temperature is high enough, the molecules split into their atomic components: silicon, iron, oxygen and so on. Later, when the vapors cool, the atoms recombine and condense on grains of moondust, depositing a layer of silicon-dioxide glass peppered with tiny nuggets of pure iron. A thin coating of iron is not enough to make sand- or gravel-sized particles noticeably magnetic, any more than spraying a thin coating of iron on a heavy basketball would make it stick to a magnet, Taylor said. A thin coating, however, is plenty for particles smaller than about 20 microns - or 20 millionths of a meter. They have so little mass compared to their surface area that they are easily attracted by the magnets. There are other ways to deal with moondust - NASA is considering a whole suite of options from airlocks to vacuum cleaners - but if Taylor is correct, magnets will prove important defenses against the material, and perhaps astronauts won't find it so troublesome next time they land. Related Links Moondust Paper UT Planetary Geosciences Institute NASA

Sacramento CA (SPX) Apr 07, 2006

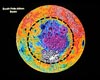

Sacramento CA (SPX) Apr 07, 2006SpaceDaily has learned that the choice for NASA's next lunar mission, to be announced on Monday, will be the "Lunar Impactor" proposed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Structured as a relatively simple spacecraft, the probe will crash into permanently shadowed craters located near the Moon's south pole. |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2006 - SpaceDaily.AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA PortalReports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additionalcopyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |